Approximately 67 miles (107 km) to the north of Aurangabad in the Indhyadri range of Western Ghats lie the caves of Ajanta. The 30 caves, famous for their early Buddhist temple architecture and many delicately drawn murals, are located in a 76 m high, horseshoe-shaped escarpment overlooking the Waghora (tiger) River. The river originates from a picturesque waterfall called sat kund (seven leaps) just off the last cave. It serves as a potent reminder of the natural forces that over untold eons have shaped the basaltic layers of the Deccan plateau. Also a part of the Gautala Wildlife Sanctuary, this primordial landscape provides a fitting background to one of the finest collections of paintings from India’s antiquity.

Accorded UNESCO World Heritage site status in 1983 CE, the ancient name of the site is untraceable today. Its current name is derived from a neighbouring village, the local pronunciation of which is Ajintha. It would be of interest to note, that Ajita is the colloquial name of Maitreya Buddha.

Timeline & Patronage

The period of excavation (used as synonymous to the carving of the caves) can be divided into two broad phases. The earliest caves (Cave 8, 9, 10, 12, 13, 15A), belonging to the Hinayana phase of Buddhism, can be roughly traced back to the 2nd century BCE, with its period of activity continuing to around the 1st century CE during the rule of Satavahana Dynasty (2nd century BCE – 2nd century CE). The later phase of activities, between 5th and 6th century CE, largely took place under the patronage of the Vakataka dynasts (3rd century – 5th century CE). The Vakatakas were contemporaries of the Gupta Empire. The greatest flourish of this phase took place during the brief but remarkable reign of the Vakataka Emperor, Harisena (460 CE – 477 CE). By then the “mythologising tendency of Indian thought” (Coomaraswamy) had already given birth to Mahayana Buddhism from more austere Hinayana practices.AJANTA HAS 30 CAVES – FIVE ARE CHAITYA (PRAYER HALL) & THE REST ARE VIHARA (MONASTERY).

The excavation and creation of the caves seem to have been a more community effort in the earlier phase. Group efforts contributed to the building of various parts of the caves, from the façades to single cells. Later, however, construction was marked by sponsorship from influential patrons and local feudatories. Inscriptions from Caves 4, 16, 17, 20, and 26 indicate that often multiple caves were constructed under the benefaction of one patron; examples would include local Risika king Upendragupta, Harisena’s Prime Minister Varahadeva, and the Asmaka monk Buddhabhadra. Royal patronage did not, however, restrict its accessibility to an exclusive clique. Thus, despite being a Shaivaite emperor (at least at the time of accession to throne), Harisena presided over the execution of some of the finest depictions of Buddhist legends.

Location & Layout

While the peaceful surroundings may be self-explanatory of the initial choice of a Buddhist monastic establishment, the caves also lay close to the ancient trade routes and capital of the Satavahana Empire, Pratishthana (currently Paithan, 130 km south of Ajanta). The rule was benevolent, commerce flourished and the cities prospered. Buddhism was already popular and Buddhist bhikshu (monks) travelled across the Deccan plateau as emissaries following Mauryan Emperor Ashoka’s (304 – 232 BCE) energetic patronage.

The caves of Ajanta were not excavated in isolation, but a range of similar activities resulted in a number of cave complexes across the Western Ghats. Some of these include the caves of Karli, Bhaja, Kanheri, Junnar, Nasik, Kondana, and Pitalkhora. It is quite possible that the inspiration for such rock-cut caves came from a set of similar structures in Barabar and the Nagarjuni Hills located in the Jehanabad district, 24 km north of Gaya. These were built during the reign of Ashoka and his grandson Dasarath (232 – 224 BCE), who succeeded him to the throne.

The permanence of rock-cut architecture compared to the prevailing free standing wooden structures and locational advantage of such dwellings were powerful arguments in favour of these experiments. The cave complex in Ajanta comprises 30 caves. Of these, five (9, 10, 19, 26, and 29) are chaitya (prayer hall with a stupa at the far end) and the rest are vihara (monastery). The caves are numbered according to their relative arrangement along the horseshoe-bend in an anti-clockwise manner from the outer end and not as per the time of excavation or purpose.

Paintings of Ajanta

The Ajanta murals, owing to their inherent fragility and an abundance of destructive natural and maleficent human agents, have suffered considerable damage, often irrevocably so. Despite the depredations, the excellent craftsmanship (specifically in Caves 1, 2, 16, 17) shines through the defiled and blackened surfaces even today. The narratives flow unrestricted from one cave wall to the next with effortless flexibility. Deep understanding of nature and profound compassion infuse each stroke and every gesture with ardour and tenderness that produces an indelible impression in the heart and mind of the beholder. It is a world of graceful movements and “serene self-possession” (Coomaraswamy) far removed from personal art of modern time. Brought to life by nameless artists, the murals trace the atman (soul) beyond verisimilitude and transient emotions, mirroring the collective social psyche.

It would be erroneous to consider that all paintings were rendered uniformly. For there are variations of style and work of minor hands comingle with chef-d’œuvre. And yet the poise, poignant faces, and expressive gestures bear infinite significance. This includes those hand signals known as mudras which are core to yoga, meditation, and Indian dance drama.

The art of Ajanta is that of a school. It is important to remember that pursuit of art for art’s sake did not constitute the sole aim and search for beauty was not an end in itself. The great religious art of Ajanta through all its sincerity and refinement acts as crucial markers towards the journey within.

Painting Technique

The rugged surface of the cave walls was made further uneven to provide a firm grip to the covering plaster made of ground ferruginous earth, rock grit, sand, vegetable fibres, paddy husk, and other fibrous materials of organic origin. A second layer of mud, ferruginous earth mixed with pulverised rock powder or sand and fine vegetable fibre helped to cover the whole interior of the cave. The surface was then treated with a thin coat of limewash over which pigments were applied. Except for the black which was obtained from kohl, all other pigments were of mineral origin. Terra verda or glauconite for green, lapis lazuli for blue, kaolin, gypsum or lime were of frequent use.

Support our Non-Profit Organization

With your help we create free content that helps millions of people learn history all around the world.BECOME A MEMBER

One of the peculiarities of the murals in Ajanta is that the power of expression depends chiefly on the swiftness of its outlines. The bold, sweeping brushstrokes portray an intimacy and sensitiveness that, even though the original lustrous colours have all but faded, reveal these to be works of adept minds and assured hands.

Painting Subjects

Jataka tales, consisting of narratives related to different incarnations of Buddha, form an abundant wellspring for a magnificent project of the scale of Ajanta. The quaint humour, distinguished gentility and earnestness which characterise this lore was a part of an oral tradition and followed irrespective of creed or allegiance. Their extensive adoption in Ajanta demonstrates an already wide acceptance among priests and populace alike.

As Buddhism evolved from earlier Hinayana to Mahayana faith, the depictions and paintings transformed. In Caves 9 and 10 the Enlightened One was represented only symbolically by the Bodhi tree, paduka (wooden footwear), wheel etc. and not pictorially. In the later phase of the development, deeply influenced by Mahayana Buddhism, murals recruit a venerable pantheon of celestial beings including Kinnara, Vidyadhara, and Gandharva among others. Ajanta then appropriately presents us with a cornucopia of beliefs, intellectual atmosphere, culture, institutions, economy, adventures, and the ways of the masses and nobility over half a millennium and more.

Sculptures of Ajanta

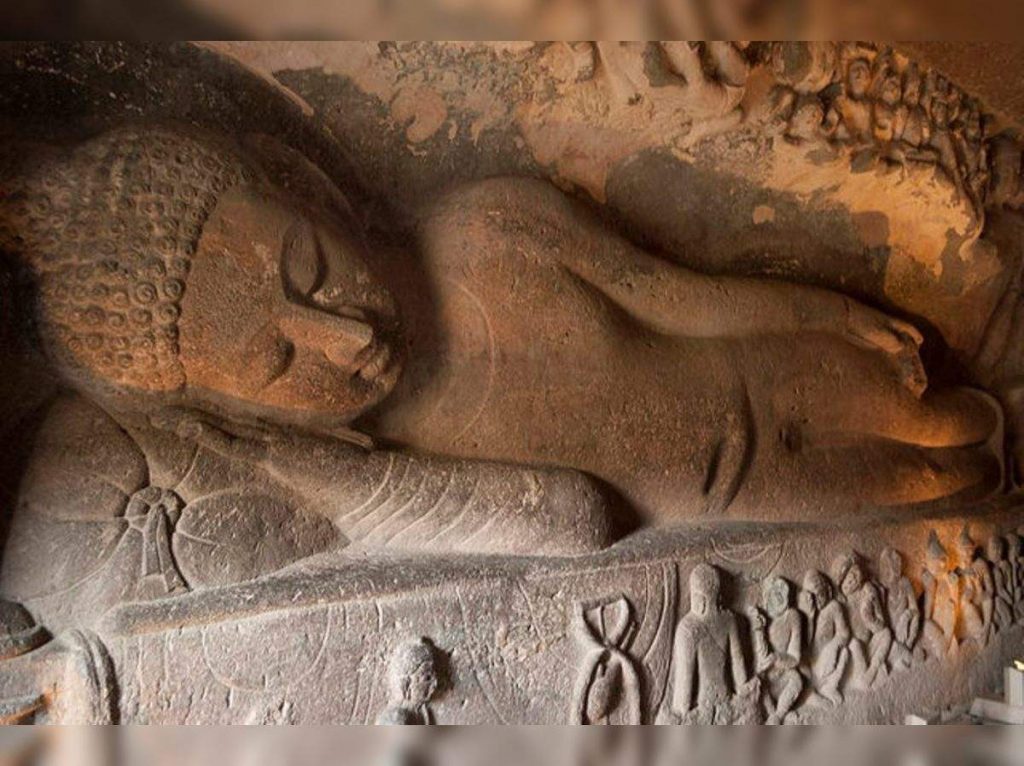

The parallels between the murals on cave walls and sculptures and sculptural motifs that adorn Ajanta are manifold. Both undergo a remarkable transformation during different phases of development, both draw inspiration from magnanimous Jataka tales, and both are equally eloquent through expressive gestures or lack thereof. Buddha as the seated yogi is the epitome of repose and stability and Buddha in abhaya mudra encourages dignified self-assurance. Besides seated forms, standing poses of no less variation and significance abound, for such subtle movements of hands and limbs communicate the impelling thought itself much more than the subsequent performance or act. So the Indian imager made extensive use of these gracious movements for a powerful impact.

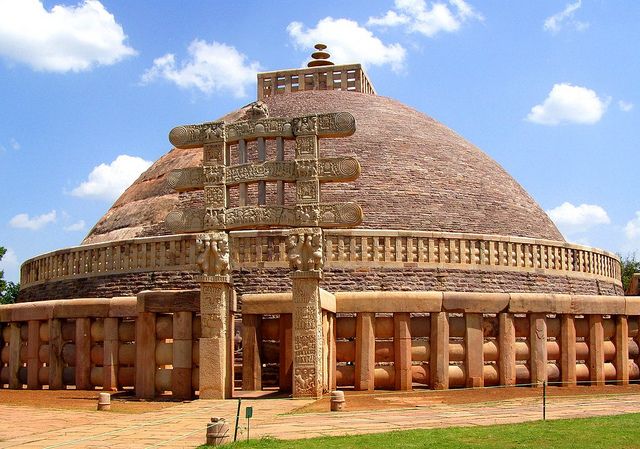

Hinayana Buddhism with its rationalistic philosophy and express prohibition of pictorial depictions of Buddha could not have inspired a metaphysical art comparable to the grandeur of the later phase. So, beyond symbolic motifs and stupa (of Caves 9, 10), little sculptural activity is observed in the caves excavated in the earlier phase.

Sculptures in Ajanta were both plastered and painted though any trace of the latter is invisible to the naked eye today. The garbha griha (sanctum sanctorum) of each vihara contains almost invariably in seated posture the figure of Buddha in dharma chakra pravartana mudra (Buddha in preaching attitude delivering his discourse). The colossal figure of Buddha in Cave 26 or the statues of Buddha that flank the entrance to Cave 19 showcase versatility in scale and narrative structure which is equally supported by delicate features and delineated forms. The façade of Cave 19 with its intricately carved pillars and pilasters, decorative motifs on rows of chaitya arches and other structural peculiarities are wonderful examples of the unison of sculpture and architecture into a harmonious whole.

Architecture of Ajanta

Much like the murals and sculptures, architectural elements too evolved continuously under differing influences and motivations. In as much as Ajanta was an application of hereditary knowledge, it was also informed by a process of constant discovery and learning, incorporation of new ideas and forms from other sites such as Bagh, and an ever-evolving artistic vocabulary. The architecture of the cave complex is unique because it reflects the ever-improving proficiency of the craftsmen, educated in an architectural style already highly developed but unfamiliar with the rock-cut medium. Ajanta in its full flourish, therefore, represents a successful integration of the splendour of contemporary structures with the peculiarities and potentials of the basaltic medium.

As previously alluded to, there are five chaityas in the cave complex with the rest being vihara. A chaitya is apsidal or rectangular in form with aisles on either side of a nave with a barrel roof. Each aisle is separated by a row of pillars. The nave contains a stupa, the object of worship, at the terminal end. The early chaityas meticulously imitated contemporary wooden structures as can be seen in the vaulted roof decorations and pillars.

In contrast to the early stupas of Caves 9 & 10, those built at later dates such as in Caves 19 & 26 have an image of Buddha sculpted on the front face. Another distinguishing feature of Cave 10 is its giant single-arched entrance and relatively unadorned façade which gives way to a smaller doorway with a window positioned above. Skilfully decorated façades and pillared porticoes testify to a definite shift in architectural activities from early austerity.

A vihara, otherwise called sangharama, was a monastic abode consisting of a central hall with adjoining residential cells. Caves 1 & 17 may be taken as the most representative example of a vihara in full development. A pillared porch or verandah with elegant embellishments leads to a commodious central hall, somewhat squarish in plan with cells for monks hewn into its sides. Further on, an antechamber connects to the garbha griha containing an image of Buddha. Thus, it can be said that architectural development proceeded from early sober, even restrained, astylar form to ambitious, richly ornamented pillared viharas.

Natural weathering agents and scarp retreat in the order of 5-7 m over the centuries have left their devastating impact on the frontispiece of many of the caves and managed to eliminate all of the stairs (except some below Cave 17) that connected each cave to the stream below.

Fall of Ajanta

The sudden discontinuation of activities in Ajanta inevitably coincides with the untimely death of Vakataka Emperor Harisena. But the seeds for disruption were sown much earlier. The provinces of Asmaka to the south of Ajanta, Anupa (where Bagh caves lie) to the north, and Risika, which included Ajanta, were inherited domains of Harisena; he did not have to conquer them. This explains the fact that within a few of years of his accession to the throne excavation work started at the site under the patronage of different vassals. It is not hard to surmise that the situation was relatively peaceful for the neighbouring rulers, despite having a belligerent history, as they came together to sponsor the projects at the same site.

This, however, did not last for long. By early 469 CE, Asmaka started a fierce battle with Risika lords. All work at Ajanta had stopped by 472 CE, and this suspension continued until late 474 CE when the Asmaka emerged victorious from the battle. From then on until the sudden death of Harisena in late 477 CE, much effort was afoot. With the passing away of the emperor, the golden years of Ajanta, too, came to an abrupt end; as chaos reigned supreme under an inept successor, violent conflicts broke out over regional supremacy, and the Vakataka Empire imploded spectacularly.

By 480 CE all excavations had ceased, most of the patrons had either been dethroned or dispossessed from their seat of power. From the sounds of chiselling and chanting, life had almost returned to a primaeval silence interrupted only by the chirping of birds or chattering of monkeys. After all, the later phase of growth at Ajanta was driven by a dozen or even less courtly patrons hoping to carve out a monument of magnificent proportions and beauty. Unlike the earlier era where it was a community effort that laid the foundation of Ajanta, this second outpour was bound to dry up with the change of fortunes of its handful of donors. In the end, what instigated its rapid expansion also forced its sudden abandonment.

After a gap of many centuries, Ajanta is again thriving with travellers, scholars, and devotees alike from across different continents. Though it no longer serves the purpose for which it was originally built, it has something to offer anyone who can spend a few moments in quiet contemplation indoors. In conclusion, the following words of renowned German archaeologist Ernst Walter Andrae (1875-1956 CE), to be found in Keramik im Dienste der Weisheit, can be used to aptly describe the significance of the art of Ajanta: “It is the business of art to grasp the primordial truth, to make the inaudible audible, to enunciate the primordial word, to reproduce the primordial images – or it is not art.”

Of the 30 caves hewn into a 250-foot rock face, five constitute the Chaityas (a Buddhist prayer hall with a stupa on one end), while the remaining are Viharas (Buddhist monastery). You can explore majority of the caves with a particularly keen eye for caves 1, 2, 16 and 17 for being the finest surviving example of ancient Indian wall-painting. Alternatively in vivid and warm colours, the murals in these caves portray Buddha’s past lives and rebirths along with rock-cut sculptures of Buddhist deities and illustrations from Jatakamala by Aryasura.

Ajanta Caves Information

If exploring the chain of caves that comprise Ajanta is on your mind, and you are wondering from where to begin, we suggest the caves that stand out for their historical and artistic excellence.

Cave 1: Lying on the eastern side of horseshoe-shaped bluff, this will invariably the first cave you will encounter while exploring the panorama of caves. The sprawling open courtyard on the facade of the cave is the reason for its steeper slope than the other caves. This was done in order to accommodate the grand facade, by cutting deep into the rock face. The artwork and the paintings in the cave, historians believe, was commissioned by Vakataka Emperor, Harishena, for the emphasis on royalty is conspicuous. Also, the Jataka tales depicted here talk about the previous births of Buddha where he was a royal. The cave in particular is breathtaking for its carved facade adorned with relief sculptures, and almost all surface is an embellished one with ornate carvings. The porch, the front court with little cells preceded by pillared antechambers, typical of the caves here in Ajanta, and the frieze over the cave with elaborate depictions of horses, bulls, elephants, lions, meditating monks and apsaras, characterise Cave 1. Apart from the architecture and detailing, it is truly the wealth of paintings adorning large portions of this cave, that leaves a visitor spellbound. Aside from scenes from Jataka tales, you have here two larger-than-life figures of the two Bodhisattvas Vajrapani and Padmapani on each side of the entrance to the Buddhist shrine.

Cave 2: Adjacent to Cave 1 is another cave whose walls, pillars and ceilings are thick with paintings. The murals portray an apparent bias for the feminine form aside from some 5th century frescoes that depict children studying in school, some listening to the teacher and the others enacting something. The carving of this cave happened between 475 and 477 CE, believed to me commissioned by a woman aide of Emperor Harishena. Unlike Cave 1’s focus on kingship, the paintings and rock carvings in Cave 2 are about powerful women playing a prominent role in the society. This cave is remarkable for its strong pillars and the carvings and paintings in all kinds of decorative themes such as human, animal, vegetation and divine motifs, with plenty of carvings dedicated to the Buddhist goddess of fertility, Hariti.

Cave 16: Ensconced smack in the middle of the site with a fleet of stairs leading into the single-storey structure is Cave 16 with two elephant figures placed on either side of the entrance. This cave was commissioned by Emperor Harishena’s minister, Varahadeva and dedicated to the community of monks. Scholars term this the ‘crucial cave’ in terms of influencing the architecture of the entire cave network of Ajanta, and for being a paradigm in understanding the chronology of the second and final phase of the construction of the cave complex. Cave 16 is a Vihara with the customary setup of a main doorway, two aisle doorways and two windows to let in some sunlight and brighten the dark interiors. The wealth of paintings in this cave will hold you in a thrall. Aside from depictions from various Jataka tales there are frescoes recounting mythological events like the miracle of Sravasti, conversion of Nanda – the half brother of Buddha, including the popular Jataka fresco of the Bodhisattva elephant that sacrificed itself to serve as food for starving people. Head to the left of the entrance and follow a clockwise pattern to follow the entire narrative. Explore scenes from the life of Buddha like the one where Sujata is offering food to Buddha robed in white carrying a begging bowl.

Cave 17: Like Cave 16, this one too has two stone elephants placed on either side of the entrance. Commissioned by Vakataka prime minister, Varahadeva and with donation from local king Upendragupta, Cave 17 is home to the greatest, and perhaps the most sophisticated, Viraha architecture. The cave also boasts of an assortment of paintings that are well-preserved, and over the years have become synonymous with Ajanta Caves. The broader theme of the frescoes here is bringing out the human virtues as mentioned in the Jataka tales with a growing attention to detail. It comprises a colonnaded porch, an array of pillars each with a unique design, a shrine in an antechamber in the heart of the cave, larger windows to let in more light, and extensive carvings of gods and goddesses from Indian mythology. With 30 important murals in Cave 17 alone including portrayal of Buddha in various postures alongside dabbling in themes as diverse as shipwrecks, lovers in throes of passion, a princess wearing makeup and a couple drinking wine together – a thread picked up from the goings-on of the early 1st millennium society, this cave is historically paramount.

Ajanta Caves Timings

The Ajanta Caves visiting hours are between 09:00 am and 05:00 pm.

Ajanta Caves Address

Ajanta Caves Road, Aurangabad, Maharashtra 431001

Ajanta Caves Opening Days

The caves are shut for the general public on Mondays.

How to Reach the Ajanta Caves

You need to arrive into Aurangabad first to explore the Ajanta Caves. Aurangabad is about 333 kilometre from Mumbai. From Aurangabad city centre, the Ajanta Caves are about 102 kilometres away on the Aurangabad – Ajanta – Jalgaon road. Hiring a local taxi is the most preferred way of making a day trip to Ajanta. But if you are driving down, you should be apprised of the fact that the highway linking Aurangabad to Mumbai is connected to other major cities in the country such as Delhi, Jaipur, Udaipur, Bijapur, and Indore.

Nearest Metro Station to Ajanta Caves

There is no metro rail availability in this area.

Nearest Bus Stand to Ajanta Caves

You can take a Maharashtra State Road Transport Corporation (MSRTC) bus that takes off from Aurangabad Central Bus Station to the north of Siddharth Garden and the Zoo, and drops you off at the Ajanta Caves entrance road. It is a 121 rupee fare from here to the caves. The cave entrance is lined with cafes, shacks, small restaurants and souvenir shops; there is a bus stand here from where you need to hop on the bus taking you to the caves site. The ride takes about 10 minutes and charges INR 16 for a non-ac bus.

Nearest Railway Station to Ajanta Caves

Jalgaon city, about 60 kilometre from Ajanta Caves is the nearest rail head. Jalgaon Junction is well connected to important cities such as Mumbai, Agra, Bhopal, New Delhi, Gwalior, Jhansi, Goa, Varanasi, Allahabad, Bangalore, Pune among others. Trains like Punjab Mail 12138, Jhelum Express 11078, Goa Express 12780 depart from New Delhi railway station / Hazrat Nizamuddin railway station and arrive into Jalgaon Junction in approx. 17 to 18 hours. If you are coming from Mumbai, the Gitanjali Express 12859 or Mahanagari Express 11093 departing from Kalyan Junction and reaching Jalgaon Junction in approx. 5 hours is a good bet. Else you can arrive into Aurangabad via train and then go on to explore the caves. Aurangabad too is decently connected to all major cities in the country, beginning with Mumbai, New Delhi, Bhopal, Agra to Gwalior.

Nearest Airport to Ajanta Caves

Aurangabad Airport, a domestic airport, about five and a half kilometre from the city centre is the closest airport to the Ajanta Caves. Air India, Jet Airways and TruJet are typically the airlines operating out of this airport. The airport has direct flights to two important cities, New Delhi and Mumbai, which further have great international connectivity. There are direct flights as well from other Indian cities like Jaipur and Udaipur.

The area near the caves have a mix of budget and boutique properties, else you can opt to stay at a hotel in Aurangabad.

Ajanta Caves Ticket Booking

Ajanta Caves entry ticket for Indian tourists is INR 40. The Ajanta Caves entry ticket price is the same for tourists from SAARC and BIMSTEC countries. However, a foreigner needs to shell out INR 600 for the Ajanta Caves ticket. The entry is free for kids under the age of 15.

Ajanta Caves Tickets Online

It is always advisable to book your monument ticket online in order to avoid waiting in long queues at the site. You can book your Ajanta Caves online ticket from the Yatra website by going onto the Monuments section from the homepage, and then feeding Ajanta Caves in your search box. The subsequent page will show up all information about the caves including the Ajanta Caves ticket price. You can add the monument to your cart and proceed to make the payment. The ASI website is another online booking platform.

During your tour of Aurangabad, it’s a good idea to cross out other significant landmarks of the likes of Bibi ka Maqbara, Aurangabad Caves and Daulatabad Fort.

Outstanding Universal Value

The Ajanta Caves in Maharashtra have found their way in the memoirs of a Mughal official of Akbar era in the early 17th century. Lost in the abounding lush green landscapes, they were accidentally discovered and were excavated in 1819 by a British colonial officer on a tiger-hunting party. They have been known to be first stated about in the chaityas and are the most ancient monuments. A major part of these caves were created in the 2nd century BC. With the downfall of the Vakataka empire in 480 AD, these caves were soon abandoned after the death of Harishena. The loyal patrons of these caves fled and Buddhist monasteries.

7 Comments

Comments are closed.