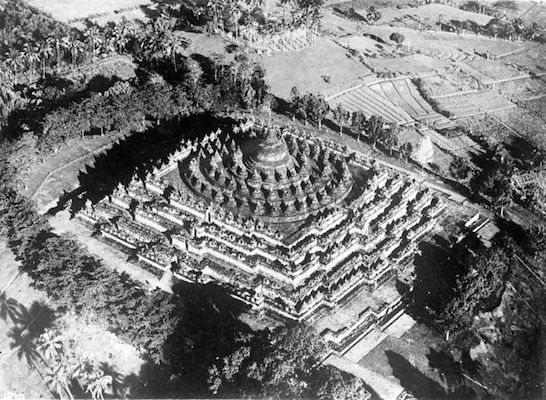

The world’s largest Buddhist monument draws pilgrims from around Southeast Asia to a remote hilltop in central Java, surrounded by lush green vegetation and ringed by volcanoes—one of which remains active.

Located on the island of Java in Indonesia, the rulers of the Śailendra Dynasty built the Temple of Borobudur around 800 C.E. as a monument to the Buddha (exact dates vary among scholars). The temple (or candi in Javanese, pronounced “chandi”) fell into disuse roughly one hundred years after its completion when, for still unknown reasons, the rulers of Java relocated the governing center to another part of the island. The British Lieutenant Governor on Java, Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, only rediscovered the site in 1814 upon hearing reports from islanders of an incredible sanctuary deep within the island’s interior. [1]

Bodobudur, photo: Wilson Loo Kok Wee (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)Bodobudur, photo: Wilson Loo Kok Wee (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)Candi Borobudur’s design was conceived of by the poet, thinker, and architect Gunadharma, considered by many today to be a man of great vision and devotion. The temple has been described in a number of ways. Its basic structure resembles that of a pyramid, yet it has been also referred to as a caitya (shrine), a stupa (reliquary), and a sacred mountain. In fact, the name Śailendra literally means “Lord of the Mountain.” While the temple exhibits characteristics of all these architectural configurations, its overall plan is that of a three-dimensional mandala—a diagram of the cosmos used for meditation—and it is in that sense where the richest understanding of the monument occurs.

Some 1,200 years ago builders carted two million stones from local rivers and streams and fit them tightly together without the aid of mortar to create a 95-foot-high (29-meter-high) step pyramid. More than 500 Buddha statues are perched around the temple. Its lower terraces include a balustrade that blocks out views of the outside world and replaces them with nearly 3,000 bas-relief sculptures illustrating the life and teachings of the Buddha. Together they make up the greatest assemblage of such Buddhist sculpture in the world.

Climbing Borobudur is a pilgrimage in itself, meant to be experienced physically and spiritually according to the tenets of Mahayana Buddhism. As the faithful climb upward from level to level, they are guided by the stories and wisdom of the bas-reliefs from one symbolic plane of consciousness to the next, higher level on the journey to enlightenment.

Borobudur was constructed in the eight and ninth centuries during the golden era of the Sailendra dynasty, which held sway on Java and neighboring Sumatra. This ruling clan came from South India or Indochina and helped to establish Java as a center of Buddhist scholarship and worship.

The magnificent site drew pilgrims for hundreds of years—Chinese coins and ceramics found there suggest that the practice continued until the 15th century. (In fact it has been revived today.)

But Borobudur was mysteriously abandoned by the 1500s, when the center of Javan life shifted to the East and Islam arrived on the island in the 13th and 14th centuries. Eruptions deposited volcanic ash on the site and the lush vegetation of Java took root on the largely forgotten site.

In the early 19th century Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, British governor of Java, heard of the site and took an interest in having it excavated. While this process revealed Borobudur’s treasures it also triggered a process of decay by exposing them to the elements. Villagers liberated stones for building materials, and collectors removed Buddha heads and other treasures for private and public collections around the world.

Fortunately, the decline of Borobudur was arrested by tighter regulations and one of the most ambitious international preservation projects ever attempted. The “Save Borobudur” campaign was launched in 1968 through the government of Indonesia and UNESCO.

The massive monument’s lower terraces were dismantled and their priceless relief panels were cleaned and treated against weathering. During this process an extensive drainage system was put in place to prevent the erosion that had taken such a toll on the temple. Over eight years a million stones were removed and later reassembled.

The result is that Borobudur remains today what it was 1,200 years ago—a unique treasure to rival any site in Southeast Asia.

History of the Temple

The story of the Borobudur Temple begins with the Shborobudur temple compounds indonesiaailendra Dynasty (sometimes spelled Syailendra). This ruling family concentrated their power in central Java in the 8th century CE, and grew to control all of Java and parts of Sumatra. Some scholars think that the Shailendra came to Indonesia from India, while others think they were native to the island. Regardless, they clearly had some cultural connections to India and were major proponents of Mahayana Buddhism, which they actively spread across Indonesia.

Their biggest achievement was the Borobudur Temple, which was built over roughly 1,200 years from the 8th through 9th centuries. What they accomplished was an engineering marvel for the time; the 95-foot tall step pyramid is made of locally sourced stone set without mortar.

For centuries, Borobudur was a major pilgrimage site, attracting the faithful from as far away as India and China. It seems to have been very popular, but then was inexplicably abandoned in the 15th century. We don’t know why Borobudur was left to be reclaimed by the jungle, but it remained lost for roughly 400 years before the colonial governor of British Java decided to have it excavated.

The excavations freed Borobudur from the jungle, but also left it open to looters. Finally, in the 1960s a massive campaign was launched by the Indonesian government and UNESCO to save and restore the site. Statues were taken out of private collections, stones were returned, and piece-by-piece Borobudur was cleaned, rebuilt, and reopened to the public. It is currently a UNESCO World Heritage Site and a stunning example of Indonesian architecture, but it has also reclaimed its role as a Buddhist pilgrimage site.

11 Comments

Comments are closed.