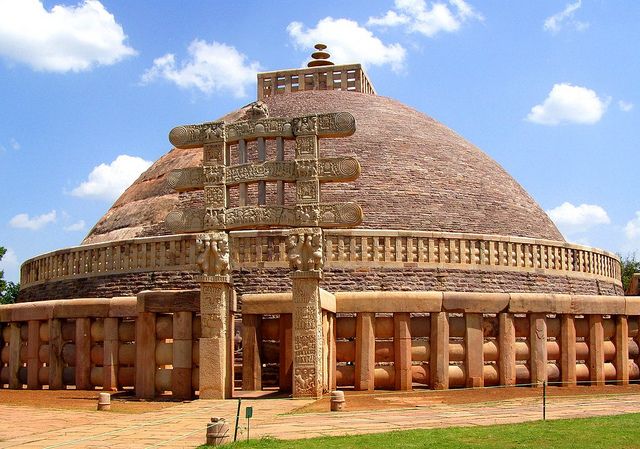

Mohenjo-daro, also spelled Mohenjodaro or Moenjodaro, group of mounds and ruins on the right bank of the Indus River, northern Sindh province, southern Pakistan. It lies on the flat alluvial plain of the Indus, about 50 miles (80 km) southwest of Sukkur. The site contains the remnants of one of two main centres of the ancient Indus civilization (c. 2500–1700 BCE), the other one being Harappa, some 400 miles (640 km) to the northwest in Pakistan’s Punjab province.

The name Mohenjo-daro is reputed to signify “the mound of the dead.” The archaeological importance of the site was first recognized in 1922, one year after the discovery of Harappa. Subsequent excavations revealed that the mounds contain the remains of what was once the largest city of the Indus civilization. Because of the city’s size—about 3 miles (5 km) in circuit—and the comparative richness of its monuments and their contents, it has been generally regarded as a capital of an extensive state. Its relationship with Harappa, however, is uncertain—i.e., if the two cities were contemporaneous centres or if one city succeeded the other. Mohenjo-daro was designated a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1980.

The city of Mohenjo-daro, now 2 miles (3 km) from the Indus, from which it seems to have been protected, in antiquity as today, by artificial barriers, was laid out with remarkable regularity into something like a dozen blocks, or “islands,” each about 1,260 feet (384 metres) from north to south and 750 feet (228 metres) from east to west, subdivided by straight or doglegged lanes. The central block on the western side was built up artificially to a dominating height of 20 to 40 feet (6 to 12 metres) with mud and mud brick and was fortified to an unascertained extent by square towers of baked brick. Buildings on the high summit included an elaborate bath or tank surrounded by a veranda, a large residential structure, a massive granary, and at least two aisled halls of assembly. It is clear that the citadel (for such it evidently was) carried the religious and ceremonial headquarters of the site. In the lower town were substantial courtyard houses indicating a considerable middle class. Most houses had small bathrooms and, like the streets, were well-provided with drains and sanitation. Brick stairs indicate at least an upper story or a flat, habitable roof. The walls were originally plastered with mud, no doubt to reduce the deleterious effect of the salts that are contained by the bricks and react destructively to varying heat and humidity.

There is no surviving evidence of architectural elaboration, though that may well have been confined to timberwork that has disintegrated. Stone sculpture, too, is scarce; some fragments, however, include the competent head and shoulders of a bearded man with a low forehead, narrowed and somewhat supercilious eyes, a fillet round the brow, and across the left shoulder a cloak carved in relief with trefoils formerly filled with red paste. Aesthetically the most notable work of figurative art from the city is a famous bronze of a young dancing girl, naked save for a multitude of armlets. Among innumerable terra-cottas the most expressive are small but vigorous representations of bulls and buffalo. Female figurines may wear elaborate headdresses, and occasional figurines of small, fat grotesques, male or female, betray what perhaps was a crude sense of humour.

Get exclusive access to content from our 1768 First Edition with your subscription.Subscribe today

The evidence suggests that Mohenjo-daro suffered more than once from devastating floods of abnormal depth and duration, owing not merely to the encroaching Indus but possibly also to a ponding back of the Indus drainage by tectonic uplifts between Mohenjo-daro and the sea. That evidence has led to speculation that Harappa may have succeeded—or at least outlasted—Mohenjo-daro.

Discovery and Major Excavations

Mohenjo-daro was discovered in 1922 by R. D. Banerji, an officer of the Archaeological Survey of India, two years after major excavations had begun at Harappa, some 590 km to the north. Large-scale excavations were carried out at the site under the direction of John Marshall, K. N. Dikshit, Ernest Mackay, and numerous other directors through the 1930s.

Although the earlier excavations were not conducted using stratigraphic approaches or with the types of recording techniques employed by modern archaeologists they did produce a remarkable amount of information that is still being studied by scholars today (see the Mohenjo-daro Bibliography).

The last major excavation project at the site was carried out by the late Dr. G. F. Dales in 1964-65, after which excavations were banned due to the problems of conserving the exposed structures from weathering.

Since 1964-65 only salvage excavation, surface surveys and conservation projects have been allowed at the site. Most of these salvage operations and conservation projects have been conducted by Pakistani archaeologists and conservators.

In the 1980’s extensive architectural documentation, combined with detailed surface surveys, surface scraping and probing was done by German and Italian survey teams led by Dr. Michael Jansen (RWTH) and Dr. Maurizio Tosi (IsMEO).

The most extensive recent work at the site has focused on attempts at conservation of the standing structures undertaken by UNESCO in collaboration with the Department of Archaeology and Museums, as well as various foreign consultants.

Details of the most recent salvage excavations and conservation are found in obscure journals or reports that are not readily available to the public, but are listed in the Bibliography for those interested in searching them out.Mohenjo-daroJonathan Mark KenoyerMohenjo Daro An Ancient Indus Valley Metropolis

In the late 1820s, a British explorer in India named Charles Masson stumbled across some mysterious ruins and brick mounds, the first evidence of the lost city of Harappa. Thirty years later, in 1856, railway engineers found more bricks, which were carted off before continuing the railway construction. In the 1920s, archaeologists finally began to excavate and uncover the sites of Harappa and Mohenjodaro. The long-forgotten Indus Valley civilization had, at last, been discovered.

Thousand of years ago, the Indus Valley civilization was larger than the ancient civilizations of Egypt and Mesopotamia combined. Many of its sprawling cities were located on the banks of rivers that still flow through Pakistan and India today. Here are a few mind-boggling facts about this civilization.

1. Oldest in the World

Scientists from IIT-Kharagpur and Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) have recently uncovered evidence that the Indus Valley civilization is at least 8,000 years old and not 5,500 years old as earlier believed. This discovery, published in the prestigious Nature journal on May 25, 2016, makes it not just older than the Egyptian and Mesopotamian civilisations but also the oldest in the world!

2. Mohenjodaro and its Great Bath

Mohenjodaro translates to the ‘Hill of the Dead’ or the ‘Mound of the Dead’ in Sindhi. The Great Bath of Mohenjodaro, a watertight pool perched on top of a mound of dirt, is enclosed within walls of baked bricks. This bathing pool (and another one at Dholavira) suggests that Harappans valued cleanliness. There are even small changing rooms surrounding the Great Bath, with an attached bath area in each room!

3. An Undeciphered Script

The most intriguing of all undeciphered scripts in the world, the Indus script is made up of partially pictographic signs and various human and animal motifs that include a puzzling ‘unicorn’. These have been found inscribed on miniature steatite seals, terracotta tablets and occasionally on metal. Linguistic experts and scientists have been trying to decipher this challenging script for decades as it could hold the key to the secrets of this mysterious culture.

4. Great Granaries Of Harappa

Evidence of several granaries, massive buildings with solid brick foundations and sockets for wooden superstructures, have been found in excavations of Harappa, Mohenjodaro, and Rakhigarhi. All the granaries were built close to the river bank so that with the help of boats, grains could be easily transported. The Great Granary at Harappa also had a series of working platforms with circular bricks nearby that were probably used for threshing grain.

5. World’s Earliest Known Dockyard at Lothal

A vital and thriving trade centre of Indus Valley civilization, Lothal had the world’s earliest known dockyard. Spanning an area 37 meters from east to west and nearly 22 meters from north to south, the dock connected the city to an ancient course of the Sabarmati river, which was the trade route between Harappan cities in Sindh and the Saurashtra peninsula. In those days, the surrounding Kutch desert of today was a part of the Arabian Sea.

6. Fire Altars of Kalibangan

Kalibangan, which literally means black bangles, lies along the left bank of the dried-up bed of river Ghaggar in Rajasthan. Other than giving the evidence of the earliest ploughed agricultural field ever revealed through an excavation, Kalibangan also has several fire altars, which suggest that the Harappans believed in the ritualistic worship of fire.

7. A Game Like Chess

Evidence suggests that the people of Indus Valley Civilization loved games and toys. Flat stones with engraved grid markings and playing pieces have been found, which shows that the Indus people may have played an early form of chess. Dice cubes with six sides and spots have also been found by archaeologists, which suggest that they may have invented the dice too.

8. Town Planning

A well-planned street grid and an elaborate drainage system hint that the occupants of the ancient Indus civilization cities were skilled urban planners who gave importance to the management of water. Wells have also been found throughout the city, and nearly every house contains a clearly demarked bathing area and a covered drainage system.

9. Urban Life

The city’s prosperity and stature are evident in the artefacts, like beads, jewellery, and pottery recovered from almost every house, as well as the baked-brick city structures themselves. Not everyone was rich but even the poor probably got enough to eat. The cities lack ostentatious buildings like palaces and temples, and there is no obvious central seat of government or evidence of a ruler. Also, the lack of many weapons shows that the Indus people had few enemies and that they preferred to live in peace.

10. A Love of Fashion

The most commonly found artefact in the Indus Valley civilization is jewellery. Both men and women adorned themselves with a large variety of ornaments produced from every conceivable material ranging from precious metals and gemstones to bone and baked clay. Excavated dyeing facilities indicate that cotton was probably dyed in a variety of colours (although there is only one surviving fragment of coloured cloth). Use of cinnabar, vermillion and collyrium as cosmetics was also known to them.

11. Intriguing Figurines

Terracotta, steatite and metal figurines of girls in dancing poses show the presence of some dance form as well as skilled craftsmanship. The most interesting and famous figurines recovered from Indus Valley excavations are the bronze Dancing Girl, the steatite Bearded Priest King and the terracotta Wheel Cart.

12. Trade Without Money

The seals and weights recovered from the ruins of several Harappan cities suggest a system of tightly controlled trade. Trade through barter (not money) was very important for the Indus civilization and their main trading partner was Mesopotamia. There is evidence that people in Mesopotamian cities like Ur owned distinctively Harappan luxury goods such as beads, pottery, weapons and tiny carved bones.

13. The Seal of Pashupati Mahadev

Thousands of engraved seals and amulets have been discovered from Harappan sites, usually made of steatite, agate, chert, copper, faience and terracotta. A famous seal displays a figure seated in a posture reminiscent of the lotus position and surrounded by animals. It depicts a revered deity of the Indus culture, Pashupati Mahadev, who is considered to be the precursor to the Vedic god Shiva.

14. Worship of Mother Goddess

It is widely accepted that the Harappan people worshipped a Mother Goddess, in addition to other fertility and phallic symbols. The recovery of a large number of Mother Goddess figurines, from almost every excavated site, suggests that Mother Goddess worship or the fertility cult was widespread and popular in the civilization.

15. Strange Burials

The evidence of the disposal of the dead at Harappa is quite unique and interesting. Excavations have yielded 57 burials of different types, in which bodies were disposed of in brick-lined rectangular or oval pits cut into the ground along with the grave goods such as jewellery, seals, and pottery. In Ropar, a man was found buried with a dog!

16. Mysterious Massacre of Mohenjodaro

Excavations down to the streets of Mohenjodaro revealed 44 scattered skeletons, sprawled on the streets as if doom had come so suddenly they could not even get to their houses. All the skeletons were flattened to the ground, including a father, a mother and a child who were found still holding hands. Lying in streets in contorted positions, within layers of rubble, ash and debris, archaeologists have concluded that these people all died by violence, but what caused the violence still remains unexplained.

17. Decline and Decay

Archaeologists have long wondered about the sudden decline of the Indus Valley civilization. There is no convincing evidence that any Harappan city was ever burned, severely flooded, besieged by an army, or taken over by force from within. It’s more likely that the cities collapsed after natural disasters or after rivers like Indus and Ghaghra-Hakkar changed their course. This would have hampered the local agricultural economy and the civilization’s importance as a centre of trade.

The continuing excavations and anthropological work have the potential to lend more insight into the disappearance of this enigmatic civilization.

15 Comments

Comments are closed.